Losing weight without rearranging your gastrointestinal anatomy carries advantages beyond just the lack of surgical risk.

The surgical community objects to the characterization of bariatric surgery as internal jaw wiring and cutting into healthy organs just to discipline people’s behavior. They’ve even renamed it “metabolic surgery,” suggesting the anatomical rearrangements cause changes in digestive hormones that offer unique physiological benefits. As evidence, they point to the remarkable remission rates for type 2 diabetes.

After bariatric surgery, about 50% of obese people with diabetes and 75% of “super-obese” diabetics go into remission, meaning they have normal blood sugar levels on a regular diet without any diabetes medication. The normalization of blood sugar can happen within days after the surgery. And 15 years after the surgery, 30% remained free from their diabetes, compared to a 7% remission rate in a nonsurgical control group. Are we sure it was the surgery, though?

One of the most challenging parts of bariatric surgery is lifting the liver. Since obese individuals tend to have such large, fatty livers, there is a risk of liver injury and bleeding. An enlarged liver is one of the most common reasons a less invasive laparoscopic surgery can turn into a fully invasive open surgery, leaving the patient with a large belly scar, along with an increased risk of wound infections, complications, and recovery time. But lose even just 5% of your body weight, and your fatty liver may shrink by 10%. That’s why those awaiting bariatric surgery are put on a diet. After surgery, patients are typically placed on an extremely low-calorie liquid diet for weeks. Could their improvement in blood sugar levels just be from the caloric restriction, rather than some sort of surgical metabolic magic? Researchers decided to put it to the test.

At a bariatric surgery clinic at the University of Texas, patients with type 2 diabetes scheduled for a gastric bypass volunteered to stay in the hospital for 10 days to follow the same extremely low-calorie diet—less than 500 calories a day—that they would be placed on before and after surgery, but without undergoing the procedure itself. After a few months, once they had regained the weight, the same patients then had the actual surgery and repeated their diet, matched day to day. This allowed researchers to compare the effects of caloric restriction with and without the surgical procedure—the same patients, the same diet, just with or without the surgery. If there were some sort of metabolic benefit to the anatomical rearrangement, the patients would have done better after the surgery, but, in some ways, they actually did worse.

The caloric restriction alone resulted in similar improvements in blood sugar levels, pancreatic function, and insulin sensitivity, but several measures of diabetic control improved significantly more without the surgery. The surgery seemed to put them at a metabolic disadvantage.

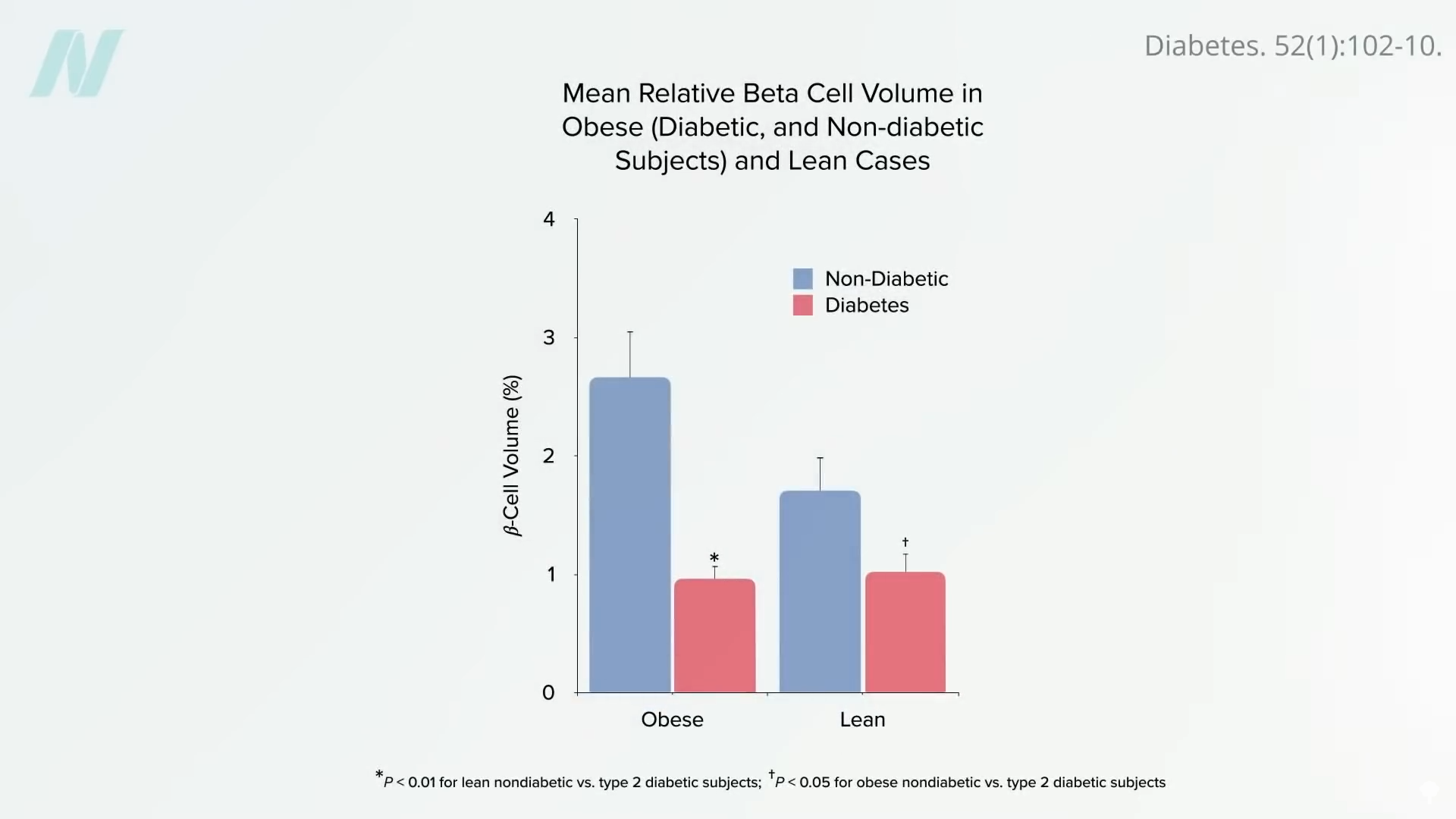

Caloric restriction works by first mobilizing fat out of the liver. Type 2 diabetes is thought to be caused by fat building up in the liver and spilling over into the pancreas. Everyone may have a “personal fat threshold” for the safe storage of excess fat. When that limit is exceeded, fat gets deposited in the liver, where it can cause insulin resistance. The liver may then offload some of the fat (in the form of a fat transport molecule called VLDL), which can then accumulate in the pancreas and kill off the cells that produce insulin. By the time diabetes is diagnosed, half of our insulin-producing cells may have been destroyed, as seen below and at 3:36 in my video Bariatric Surgery vs. Diet to Reverse Diabetes. Put people on a low-calorie diet, though, and this entire process can be reversed.

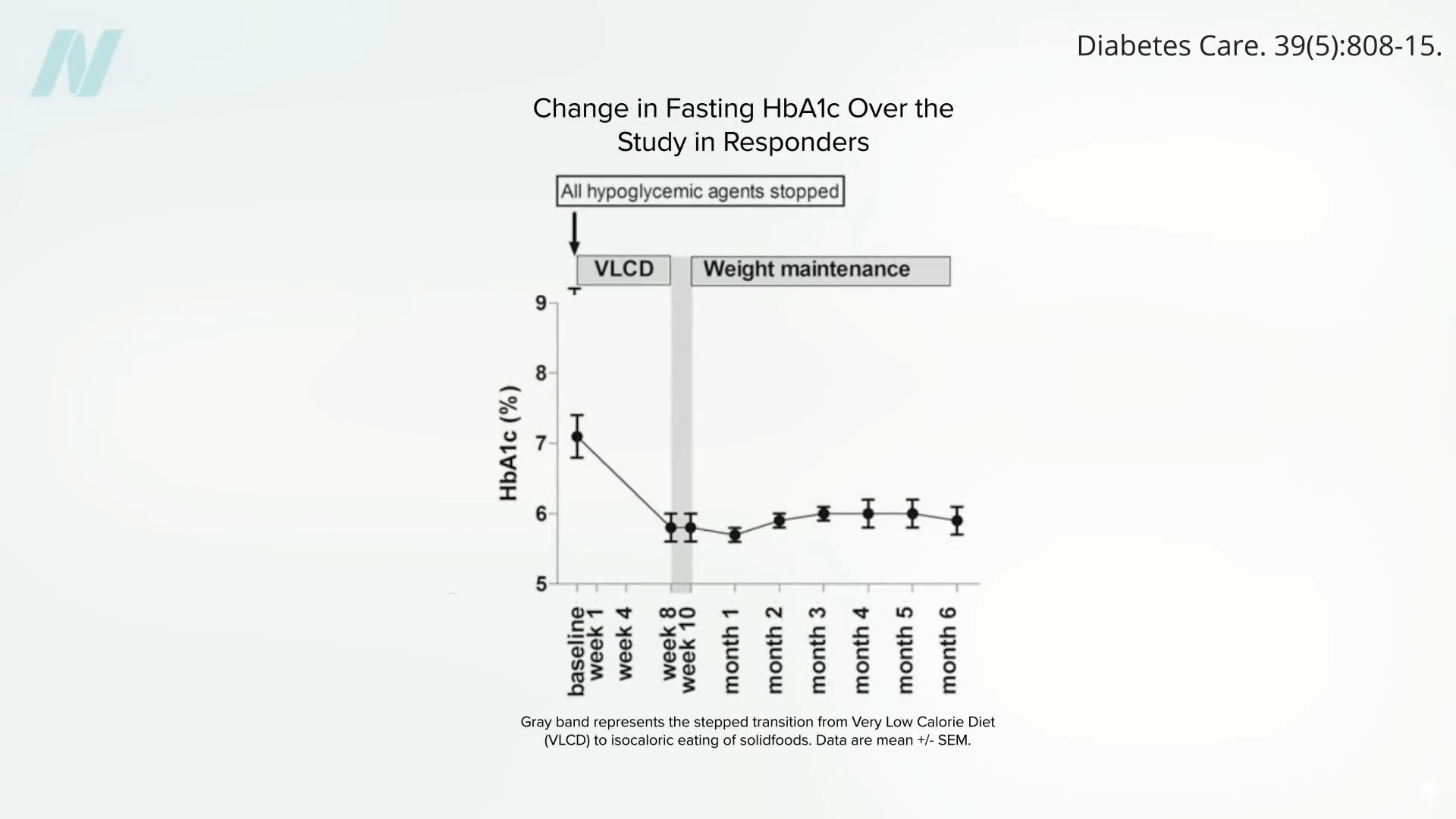

A large enough calorie deficit can cause a profound drop in liver fat sufficient to resurrect liver insulin sensitivity within seven days. Keep it up, and the calorie deficit can decrease liver fat enough to help normalize pancreatic fat levels and function within just eight weeks. Once you drop below your personal fat threshold, you should then be able to resume normal caloric intake and still keep your diabetes at bay, as seen below and at 4:05 in my video.

The bottom line: Type 2 diabetes is reversible with weight loss, if you catch it early enough.

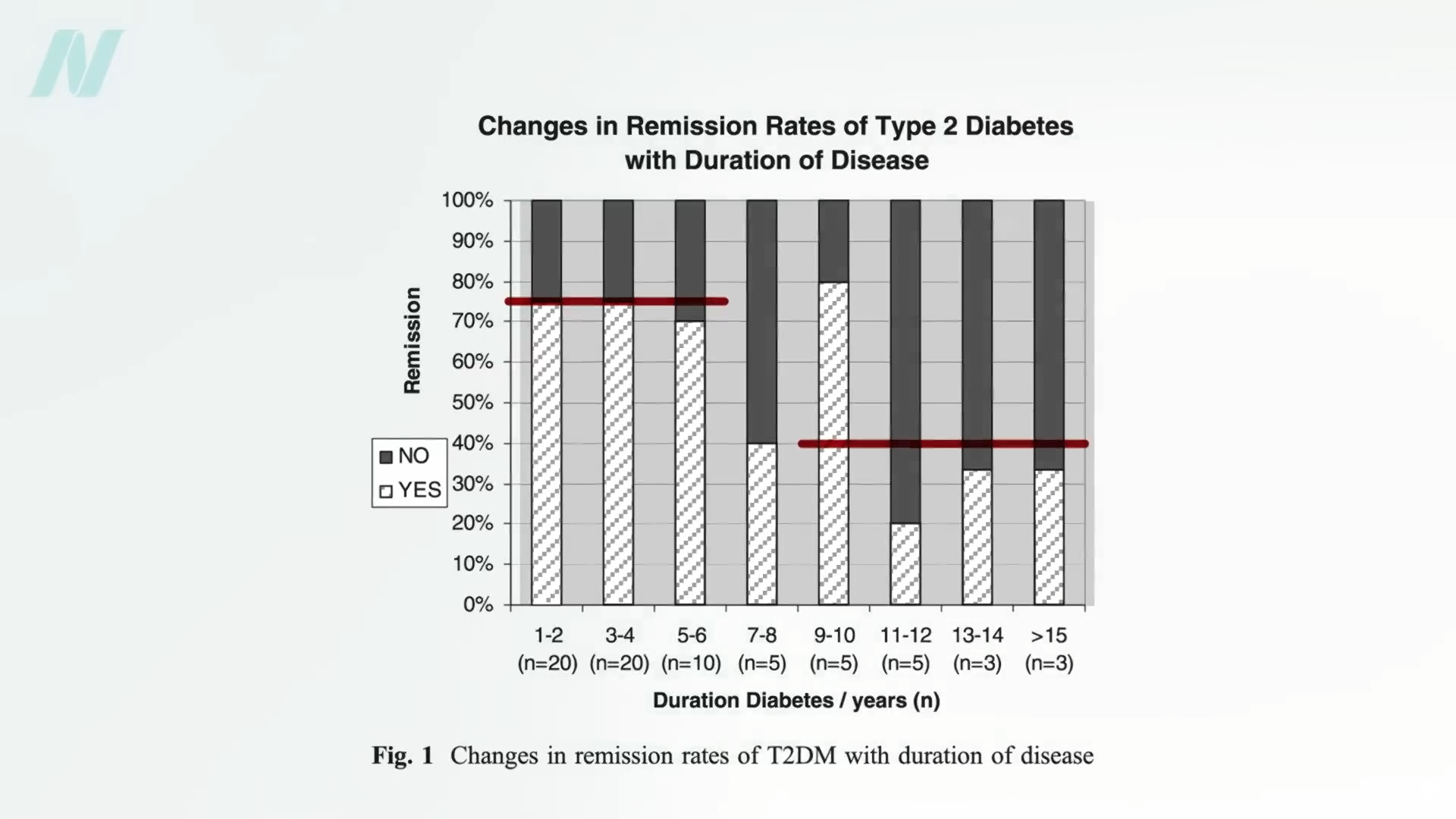

Lose more than 30 pounds (13.6 kilograms), and nearly 90% of those who have had type 2 diabetes for less than four years can achieve non-diabetic blood sugar levels (suggesting diabetes remission), whereas it may only be reversible in 50% of those who’ve lived with the disease for eight or more years. That’s by losing weight with diet alone, though. For people with diabetes, losing more than twice as much weight with bariatric surgery, diabetes remission may only be around 75% of those who’ve had the disease for up to six years and only about 40% for those who’ve had diabetes longer, as seen below and at 4:41 in my video.

Losing weight without surgery may offer other benefits as well. Individuals with diabetes who lose weight with diet alone can significantly improve markers of systemic inflammation, such as tumor necrosis factor, whereas levels significantly worsened when about the same amount of weight was lost from a gastric bypass.

What about diabetic complications? One reason to avoid diabetes is to avoid its associated conditions, like blindness or kidney failure requiring dialysis. Reversing diabetes with bariatric surgery can improve kidney function, but, surprisingly, it may not prevent the occurrence or progression of diabetic vision loss—perhaps because bariatric surgery affects quantity but not necessarily quality when it comes to diet. This reminds me of a famous study published in The New England Journal of Medicine that randomized thousands of people with diabetes to an intensive lifestyle program focused on weight loss. Ten years in, the study was stopped prematurely because the participants weren’t living any longer or having any fewer heart attacks. This may be because they remained on the same heart-clogging diet but just in smaller portions.

Doctor’s Note

This is the third blog in a four-part series on bariatric surgery. If you missed the first two, check out The Mortality Rate of Bariatric Weight-Loss Surgery and The Complications of Bariatric Weight-Loss Surgery.

My book How Not to Diet is focused exclusively on sustainable weight loss. Check it out from your local library, or pick it up from wherever you get your books. (All proceeds from my books are donated to charity.)