Smoking cannabis may help with symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the short term, but it may make the long-term prognosis worse.

As this study asks, “Medical Marijuana: A Panacea or Scourge?” For 5,000 years, cannabis “has been used throughout the world medically, recreationally, and spiritually.” It was even prescribed by American physicians “for a plethora of indications” from the mid-19th century to the 1930s, a fact that’s often used by medical marijuana proponents as evidence justifying the modern medical applications.” But the field of old-timey medicine is “fraught with potions and herbal remedies,” not to mention bloodletting and other questionable and harmful remedies.

Skeptics criticize the medical marijuana movement as the “‘medical excuse marijuana’ movement,” insinuating that children with epilepsy and the terminally ill are being “used as a ‘Trojan horse’ for the legalization of recreational cannabis use” or to peddle “outlandish claims” about “miracle cancer cures,” frustrating researchers in the field who just want to get at the science.

For example, what about the therapeutic use of cannabis for inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis? Conventional therapies work mainly by suppressing the immune system to try to tamp down inflammation. “Given the limited therapy options and known adverse side effects with chronic use” from these drugs, people suffering from these diseases often need to have inflamed sections of their bowels removed surgically, so it’s clear why there’s so much interest in alternative approaches.

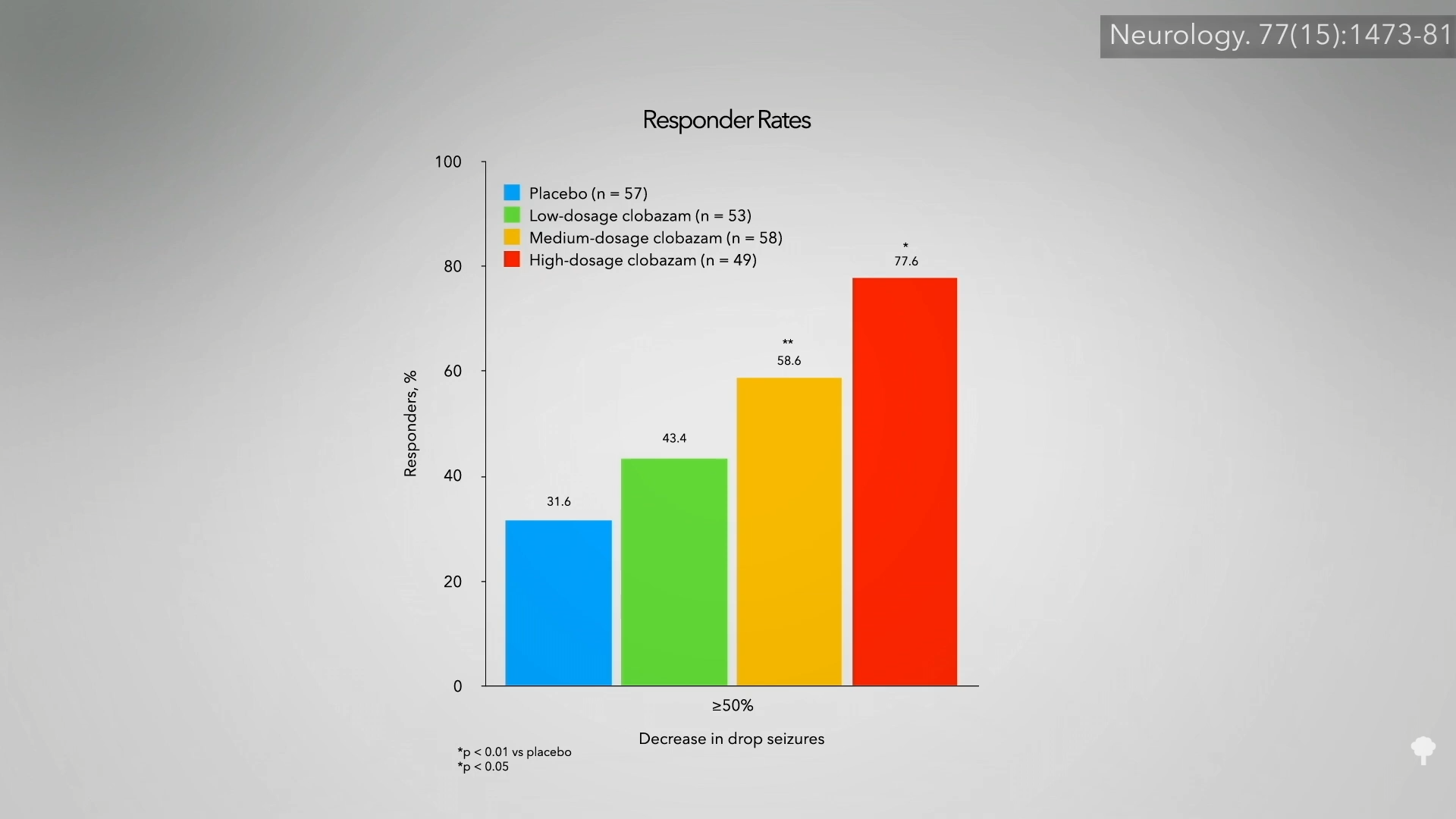

About one in six IBD patients who use marijuana say it helps with their symptoms, so researchers decided to put it to the test. Thirteen patients with IBD were given a third of a pound of marijuana to smoke at their leisure over a period of three months, and they reported feeling significantly better with “reported improvement in general health perception, social functioning, ability to work, physical pain, and depression.” There wasn’t a control group, so it’s unknown if they would have improved anyway or what role the placebo effect may have played. It’s like some of the studies of cannabis used for pediatric epilepsy that had response rates exceeding 30 percent and a frequency cut in half in a third of the kids. Amazing results until you realize you can sometimes get similarly amazing responses from giving kids nothing but a sugar pill placebo, as seen below and at 2:21 in my video Friday Favorites: Cannabis for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). That’s why it’s critical to do randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, but there weren’t any on cannabis and IBD until 2013.

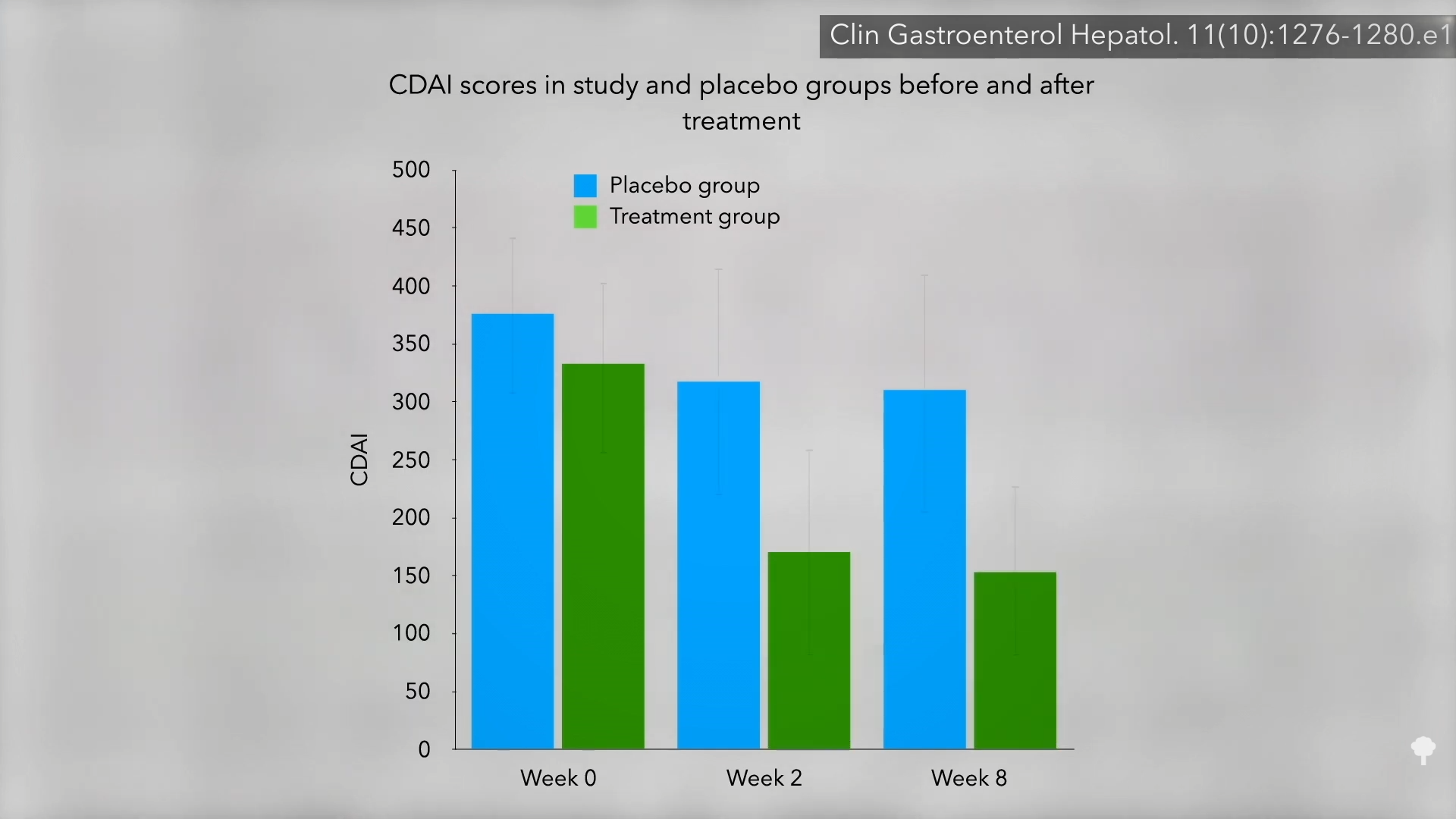

For 21 patients with Crohn’s disease, nothing seemed to help. So researchers randomized them to either smoke two joints a day of marijuana or a look-alike placebo. The results? Ninety percent of those in the cannabis group got better, compared to only 40 percent in the placebo group. Shown below and at 3:11 in my video is a graph of their symptom scores. As you can see, there was no big change in the placebo group over the two-month study, but the cannabis group cut their symptoms by about half.

The researchers acknowledge that long-term cannabis use is not without risks, but it may be a cakewalk compared to the potential adverse—and even life-threatening—side effects of some of the more powerful conventional therapies, so the study was heralded in a paper entitled “High Hope for Medical Marijuana in Digestive Disorders.”

The study was funded by a medical marijuana advocacy organization, the main supplier in the country, in fact. So, expectations may have been placed on the participants about how much better they would feel—in other words, they may have been primed for the placebo effect. But the researchers controlled for that, right? Those getting the real cannabis did significantly better than those randomized to get the placebo. But the point of a placebo is that it is indistinguishable from the real thing, so the participants don’t know which group they’re in—the control group or the treatment group. How can that be accomplished with a psychoactive drug? It can’t, which is the problem. The researchers tried to hide which group participants were in by only recruiting patients who had never tried cannabis before in the hopes that they wouldn’t notice placebo pot, but, unsurprisingly, most of them did. So, we’re basically left with another unblinded study. The researchers asked a bunch of subjective questions, like “How are you feeling?” and those who pretty much knew they were taking the drug said they were feeling better.

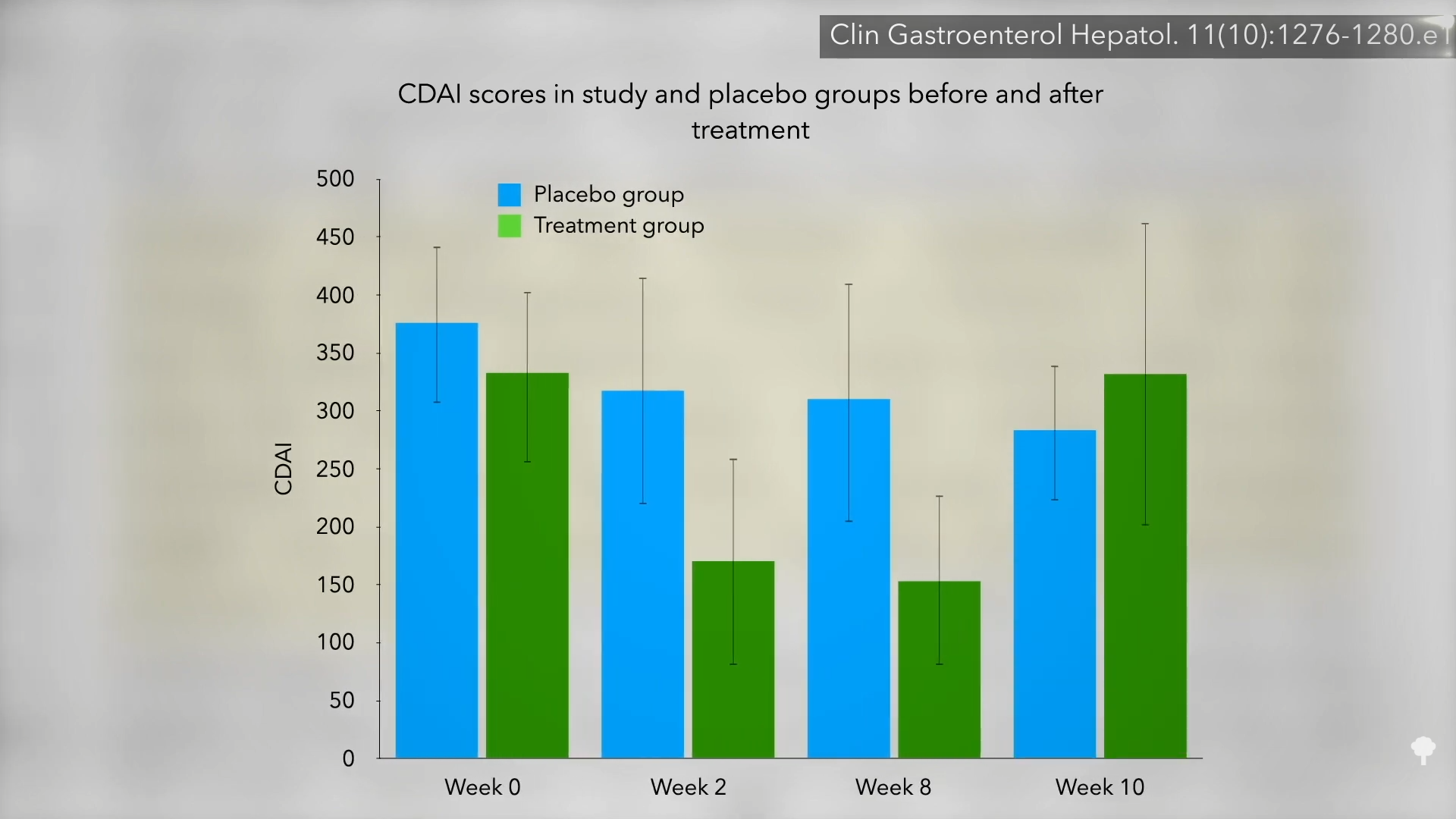

There were no significant changes in objective lab values, like CRP, a sign of inflammation, so perhaps the “cannabis may simply be masking symptoms without affecting intestinal inflammation.” Another indicator that it may not be affecting the course of the disease itself is how quickly the symptoms rebound. Two weeks after the study ended, those in the cannabis group were right back to where they started, as shown here (see week 10) and at 5:05 in my video.

So, “there was no difference in objective inflammatory markers to indicate disease modification. Given the rapid rebound…to pretreatment levels after the 2-week washout period, it seems more plausible that cannabis ameliorated the symptoms of Crohn’s disease, rather than actually modulating the disease.” That may be, but the symptoms are terrible. A reduction in pain is a reduction in pain. Indeed, “from the point of view of the patients, a marked symptomatic improvement and ability to resume normal life is not trivial, even if inflammation persists.” Of course, what if cannabis somehow makes the disease worse in the long run?

A survey study published the following year found that cannabis provided the same immediate symptomatic relief but was associated with a worse disease prognosis over time. Patients with IBD reported that cannabis improved their pain, cramping, and diarrhea, but use for more than six months by Crohn’s patients appeared to be a strong predictor of them ending up in surgery; they had five times the odds of going under the knife. There are two possible explanations for this: It’s quite possible that the increased disease severity led to the cannabis use and not the other way around. The alternative explanation: “Cannabis use may worsen the prognosis of IBD, leading to greater surgeries and hospitalizations.”

This is why we need prospective clinical trials where people are followed over time to see which came first. Until then, perhaps we should consider cannabis use for IBD as “potentially harmful.” Not just to err on the side of caution, but because there was a study on hepatitis C patients that found that daily cannabis use was associated with nearly seven times the odds of worse liver fibrosis, which is like scar tissue. If cannabis really does make fibrosis worse, that may explain why cannabis users with IBD may be more likely to require surgery.